Monday, December 1, 2008

What Shall We Give the Children?

We saw a piece in the newspaper that helped us make sense of this.

The article explained that children’s toys, if they are good toys, are tools to unlock the imagination. This unlocking is what Jean Piaget called a “transformation,” by which children “bend the world to the service of desire.”

What we got out of that was that a paper bag was a good toy, because you can make it a hat, a boat, a basket, a grotto devoted to the Virgin Mary. Anything you please. Whereas a cowboy hat is only a cowboy hat, and the more it is a cowboy hat the less it can be anything else. Therefore it is a bad toy, and will probably immobilize any child who puts it on his head.

(Now it does occur to us that an imaginative child—what might even seem to be a bad child, if there is any such thing—might think of some other uses for a hat than putting it on the head. Some of these uses might ruin the thing as a hat, but would thereby increase its value as a toy. In any case, the hat would be transformed.)

Let us therefore write down to give all the little children paper bags and coat hangers for Christmas this year. And blocks, finger paints, clay, story books with lots of pictures, building sets, microscopes, hammers, glue, scissors, colored paper, and, naturally, soup.

Saturday, November 22, 2008

Creativity Begins In . . .

Creativity begins in dissent. I heard someone say that a long time ago and believed it. But now I am not so sure.

Creativity begins in dissent. I heard someone say that a long time ago and believed it. But now I am not so sure. The print was “The Bath” by Mary Cassatt. As I made my quick little copy, I saw the care with which Cassatt had composed her painting.

Look at the care with which the bodies of the woman and girl are disposed. The negative space made by the girl’s legs is mirrored by the space made by the woman’s arm and the girl. The woman’s hand and arm are mirrored in the girl’s hand and arm. The girl’s other arm is crooked to hold the woman’s knee: the woman’s arm is crooked to hold the girl. Both faces look down at the large hand and the small foot in the basin. Their postures are in fact identical. And yet they are two separate people. Their hair color is different, their skin tones, their features. (You cannot see this in my little copy. Go to the link.)

It seems more likely that Mary Cassatt had simply found something she loved looking at and put this care and attention into this painting so someone else could see it, too.

As for dissent—lots of creativity surely begins there, as well as in anger, outrage, hatred, disillusionment, despair. As well as in playfulness, maddness, religious rapture, crankiness, and many other things you might name. But I am putting away the notion that any one of these things, and it alone, drives creativity.

Friday, November 14, 2008

How I Learned To Make Banana Bread

Thursday morning I made banana bread by a recipe Annika and I saw on Boosh Koosh. We had been having a bagel in the kitchen when she saw the DVD on the table and asked for it. I had been wanting to draw a picture of her awake, but she had never been still long enough. I thought if I put the DVD in, I might have time to get off a quick drawing.

Thursday morning I made banana bread by a recipe Annika and I saw on Boosh Koosh. We had been having a bagel in the kitchen when she saw the DVD on the table and asked for it. I had been wanting to draw a picture of her awake, but she had never been still long enough. I thought if I put the DVD in, I might have time to get off a quick drawing.We watched a particularly powerful episode where the blue dog and a young man named Joe dress up and do “Little Red Riding Hood.” The recipe was in a kitchen sequence, when Riding Hood was packing her basket for Grandmother.

The director presented the recipe in pictographs: pictures of three bananas, two eggs, one stick butter. There was even a simple animation showing how you peel the bananas and drop them whole into the bowl.

Friday the Thirteenth Was on a Thursday This Month

Thursday, October 30, 2008

All a Dream

I dreamed that it was the middle of the night, and I was lying in bed dreaming. All at once five or six people came into my room. I knew they were Republicans. One of them was solid and chunky, and he had a plastic I.D. card pinned to his suit. He demanded an explanation: “Why are you not voting for John McCain!”

I should be telling my shrink about this, and I will, as soon as I can get in to see him. I have this kind of dream every so often. Usually it is someone demanding that I explain my religious beliefs—not a secular guy who thinks religious claims are false, but a fundamentalist from my home town in Alabama who thinks it wrong to read the Revised Standard Version. Last night’s dream was a variation on the theme.

I stammered out Reason Number One: “Sarah Palin!”

I was about to give another reason, but the man in the suit was already arguing with me about my first reason. I felt foolish. Well, how would you feel if you had to sit up in your own bed in the middle of the night and defend yourself to five or six fully dressed Republicans?

That is why I hate to dream. I am always having bad dreams. Dreams about politics and religion. Dreams about missing class for a whole semester. Dreams about public bathrooms with wet floors and all the places taken.

You’d think that at my admirable stage in life I was entitled to a few good dreams. Drawing a sheep and getting the lines right. Running tirelessly through fields of endless poppies. Being asked a question and getting the answer.

But no. I would wake and find it was all a dream. The sheep is crooked, my back is tired, and the answer escapes me.

However, I will keep on drawing crooked sheep and trees that look like broccoli. I will still walk everywhere I can. I will still give my own answers and not anybody else’s and be wrong and so what. I will still vote for whoever I want to. And I will get a bumper sticker for my car that says, “I am not afraid.”

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Views of the Common Man

The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.

The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Madame Blavatsky’s Dog and the Current Crisis

Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.

Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.Tuesday, September 16, 2008

My Foreign Policy Experience in Luxembourg

I got one the other day when I read about Sarah Palin’s foreign policy experience. The paper said that the Alaska governor had made a trip to Iraq and Kuwait to visit Alaskan Reserves and had visited a couple of other countries, too, including Ireland.

Well, the colonel of the reserves was pretty sure Governor Palin hadn’t actually gone into Iraq: she didn’t have permission to cross the border from Kuwait. But she had apparently got close enough to where she could get a good look at it, which is like seeing Russia from Alaska, or New Hampshire from Brattleboro, or seven states from Rock City.

But it was the governor’s experience in Ireland that was real fresh air for me. Her plane had put down for a refueling stop, and she had remained aboard until it took off again.

As I thought about this, I realized that getting foreign policy experience is not as hard as I once believed. I realized, in fact, that I myself have enough experience to be a U.S. ambassador to Luxembourg. Indeed, I am awash with experience, because I have been to Luxembourg six times.

I made each of these six visits during the course of three round-trips between Basel and Brussels. Basel is the Swiss university town and pharmaceutical hub on the Rhine—a river which I have picked up so many rocks from the banks of that they fill a small saucer on my window sill. Brussels lies at the end of my three round trips to it, a city with three train stations in a broad, flat, partly French-speaking country which is not however France.

But to return to Luxembourg—My foreign policy experience there has prepared me for my ambassadorship by giving me two key concepts.

The first is that whereas the train goes into Luxembourg head first, it comes out hind part before. This fact so astonished me on my first visit, that I thought I had merely forgotten which way the seats in the car were facing. But the fact was confirmed on my second visit, and by the time I made my sixth trip to Luxembourg, it had become a commonplace.

The second key concept follows logically from the first: the country of Luxembourg is not big enough to turn a train around in.

You may by now be thinking, Broyles, you will not be the only person in line for the Luxembourg ambassadorship. True. But not to worry. I have Plan B: an ambassadorship to Canada. My parents visited Niagara Falls one time on the Canadian side and called me from a pay phone, and I could hear the falls over the telephone.

Keep your eye on this blog. I’ll post my foreign mailing address.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Truth and the Red Bar

Yesterday several of us drove to

When we turned into the main gate to

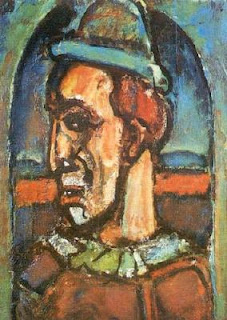

Steve Schlosser at the McMullen had put together a wonderful exhibit of work by Georges Rouault. Steve walked us through the rooms in chronological order and told us things and then turned us loose to go back and look more closely.

Everything looked sad and dark. Tears were “at the heart of everything”: an old clown whose age couldn’t be hidden by paint any more, a washed-up prostitute who still had to pretend she was a joy-girl, judges in tight collars too stupid to hand down just decisions. The face of Christ was everywhere, immeasurably sad, with eyes almost always closed, like the image pressed into Veronica’s handkerchief.

Then Steve took us into the next room and showed us that in 1930 a new element started showing up in Rouault’s pictures. It was a horizontal red line, like the balance-bar in a ballet school. Rouault put it behind clowns, acrobats, dancers—people who were liable to lose their balance and fall.

It was Rouault’s way of saying that even in a world racked by instability—and Steve showed us that Rouault’s was: born in 1871 in the cellar of a house that was being shot up by artillery, lived in France during World War I, fled south during World War II when the Nazis occupied Paris, knew all about the extermination camps and the Bomb and the cold war (he died in 1958)—even in a world racked by instability and miseries and tears, there is a red line of redemption, and this, as much as the tears, is a part of the truth of our experience.

It is hard to tell the truth.

Artists in the twentieth century sought like anything to tell the truth. That is why so many of their images are distorted and ugly. It was a distorted and ugly century. Most artists didn’t see any redemption in it, which is okay, because it can be hard to see. But what isn’t okay is the reflexive rejection of someone else’s vision of redemption just because I can’t see it. Artists do this as much as anyone else. Maybe that is partly why—as Sandra Bowden pointed out to us—Rouault was dropped from the sixth edition of Janson. It is sometimes hard for even artists to tell the truth and get elected.

On the drive back from

Thank the dear Lord that Rouault got it right. The misery and instability and danger of falling. The red balance bar at our hips.

Friday, September 12, 2008

McCain and Technology

It is amazing how things work out. The other day I wrote to my sister in an email that I couldn’t decide whether to go to the barber shop that day or the day after. I went the day after, and it is amazing how things worked out.

It is amazing how things work out. The other day I wrote to my sister in an email that I couldn’t decide whether to go to the barber shop that day or the day after. I went the day after, and it is amazing how things worked out. Thursday, January 31, 2008

Does Reading Last?

“It makes them feel happy and relaxed,” Fernando said, “but it doesn’t last.”

Next day Laurel asked about reading: “Does it last longer than TV?”

Until Fernando and I can get funding to find out, I will deliver my hunch: yes, it lasts a great deal longer. Or it can, anyway.

I still remember the pleasure I got out of reading Robinson Crusoe when I was fifteen, lying on the kitchen floor with my head propped against the washing machine. And the feeling of divine discontent and longing I got reading The Wind in the Willows when I was sixteen and about thirty more times since then. And the sudden quivering jolt I felt in my spinal column reading E. D. Hirsch’s Validity in Interpretation at thirty-eight.

Then Laurel’s husband, Chris, asked, “And how did you feel watching It’s an Incredible Life?”

Hmm. I’m sure I felt good. But I don’t remember it.

“It’s because when you read, you become that character,” Laurel said. Surely that can be emotionally affecting. And I think there is something more, too.

Here’s what I think. Reading lasts—especially reading complex enough to engage you to the tip-end of your spine—because it takes so much work.

Television takes a little work, too. You have to pay attention a little bit, you have to remember a little bit. But as a genre, ordinary television programming doesn’t work you too hard. The canned laughter tells you when it’s funny, the actor’s voices tell you when they are sincere or sarcastic, the flash-backs remind you that the murder was done with a bullet to the brain.

Movies work you harder. I am talking about the complex ones, the arty ones. You have to pay attention more closely and remember more carefully and think more. Two weeks after watching Blowup you might still be trying to figure out what was real and what wasn’t.

Reading works you harder still. You have to construct the whole she-bang as you go along. You have to decode a sequence of alphabetic characters and construe grammar and build up a context and look words up in a dictionary.

You have to figure out that the names Alyosha and Alexey refer to the same person, and you have to remember that Dmitri is the only son who believed he had property.

You have to know that Aphrodite, Ares, and Apollo side with the Trojans and Hera, Athena, and Poseidon side with the Achaians, that these are gods and goddesses, not men and women, and that Ares is a two-face.

You have to realize when something is comic. When the spotted ponies begin walking through people’s houses, you must decide whether this is hilarious or merely incomprehensible.

Sometimes you have to supply a central fact of the story, because the author makes you work even for that: that the man taking the fishing trip is a traumatized war veteran. And sometimes a central fact is not even a fact but an unresolved dilemma: does the terrified boy who climbed to the top of the water tower climb down again?

Now what were we talking about? It started with television’s drug effect—drugs don’t last—and then there was something about the effects of books lasting, sometimes, for a very long time. Yes. And that reading, good reading, is work, because the author constructs a whole world, puts it into code, and then you have to reconstruct it with your own brain if you are ever going to get it at all.

Ah. And getting it is the whole point of doing it, because we become more than we were before.