Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.

Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Madame Blavatsky’s Dog and the Current Crisis

Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.

Monday my sister and I had lunch in Philadelphia with a colleague of mine named Bert. We met at the White Dog Cafe on Sansom Street, amid the University of Pennsylvania in a block that was originally a row of brownstone residences. During the early months of 1875, Madame Blavatsky lived in the house that is now the White Dog Cafe.Tuesday, September 16, 2008

My Foreign Policy Experience in Luxembourg

I got one the other day when I read about Sarah Palin’s foreign policy experience. The paper said that the Alaska governor had made a trip to Iraq and Kuwait to visit Alaskan Reserves and had visited a couple of other countries, too, including Ireland.

Well, the colonel of the reserves was pretty sure Governor Palin hadn’t actually gone into Iraq: she didn’t have permission to cross the border from Kuwait. But she had apparently got close enough to where she could get a good look at it, which is like seeing Russia from Alaska, or New Hampshire from Brattleboro, or seven states from Rock City.

But it was the governor’s experience in Ireland that was real fresh air for me. Her plane had put down for a refueling stop, and she had remained aboard until it took off again.

As I thought about this, I realized that getting foreign policy experience is not as hard as I once believed. I realized, in fact, that I myself have enough experience to be a U.S. ambassador to Luxembourg. Indeed, I am awash with experience, because I have been to Luxembourg six times.

I made each of these six visits during the course of three round-trips between Basel and Brussels. Basel is the Swiss university town and pharmaceutical hub on the Rhine—a river which I have picked up so many rocks from the banks of that they fill a small saucer on my window sill. Brussels lies at the end of my three round trips to it, a city with three train stations in a broad, flat, partly French-speaking country which is not however France.

But to return to Luxembourg—My foreign policy experience there has prepared me for my ambassadorship by giving me two key concepts.

The first is that whereas the train goes into Luxembourg head first, it comes out hind part before. This fact so astonished me on my first visit, that I thought I had merely forgotten which way the seats in the car were facing. But the fact was confirmed on my second visit, and by the time I made my sixth trip to Luxembourg, it had become a commonplace.

The second key concept follows logically from the first: the country of Luxembourg is not big enough to turn a train around in.

You may by now be thinking, Broyles, you will not be the only person in line for the Luxembourg ambassadorship. True. But not to worry. I have Plan B: an ambassadorship to Canada. My parents visited Niagara Falls one time on the Canadian side and called me from a pay phone, and I could hear the falls over the telephone.

Keep your eye on this blog. I’ll post my foreign mailing address.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Truth and the Red Bar

Yesterday several of us drove to

When we turned into the main gate to

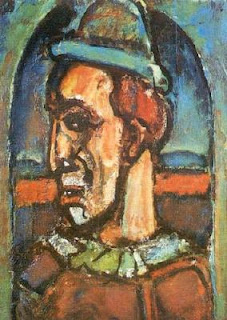

Steve Schlosser at the McMullen had put together a wonderful exhibit of work by Georges Rouault. Steve walked us through the rooms in chronological order and told us things and then turned us loose to go back and look more closely.

Everything looked sad and dark. Tears were “at the heart of everything”: an old clown whose age couldn’t be hidden by paint any more, a washed-up prostitute who still had to pretend she was a joy-girl, judges in tight collars too stupid to hand down just decisions. The face of Christ was everywhere, immeasurably sad, with eyes almost always closed, like the image pressed into Veronica’s handkerchief.

Then Steve took us into the next room and showed us that in 1930 a new element started showing up in Rouault’s pictures. It was a horizontal red line, like the balance-bar in a ballet school. Rouault put it behind clowns, acrobats, dancers—people who were liable to lose their balance and fall.

It was Rouault’s way of saying that even in a world racked by instability—and Steve showed us that Rouault’s was: born in 1871 in the cellar of a house that was being shot up by artillery, lived in France during World War I, fled south during World War II when the Nazis occupied Paris, knew all about the extermination camps and the Bomb and the cold war (he died in 1958)—even in a world racked by instability and miseries and tears, there is a red line of redemption, and this, as much as the tears, is a part of the truth of our experience.

It is hard to tell the truth.

Artists in the twentieth century sought like anything to tell the truth. That is why so many of their images are distorted and ugly. It was a distorted and ugly century. Most artists didn’t see any redemption in it, which is okay, because it can be hard to see. But what isn’t okay is the reflexive rejection of someone else’s vision of redemption just because I can’t see it. Artists do this as much as anyone else. Maybe that is partly why—as Sandra Bowden pointed out to us—Rouault was dropped from the sixth edition of Janson. It is sometimes hard for even artists to tell the truth and get elected.

On the drive back from

Thank the dear Lord that Rouault got it right. The misery and instability and danger of falling. The red balance bar at our hips.

Friday, September 12, 2008

McCain and Technology

It is amazing how things work out. The other day I wrote to my sister in an email that I couldn’t decide whether to go to the barber shop that day or the day after. I went the day after, and it is amazing how things worked out.

It is amazing how things work out. The other day I wrote to my sister in an email that I couldn’t decide whether to go to the barber shop that day or the day after. I went the day after, and it is amazing how things worked out.