The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.

The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Views of the Common Man

The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.

The hardest part about drawing trees is seeing them properly, and finally I decided to do something about it.Sunday, September 14, 2008

Truth and the Red Bar

Yesterday several of us drove to

When we turned into the main gate to

Steve Schlosser at the McMullen had put together a wonderful exhibit of work by Georges Rouault. Steve walked us through the rooms in chronological order and told us things and then turned us loose to go back and look more closely.

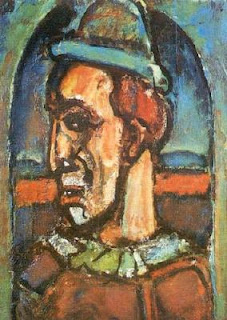

Everything looked sad and dark. Tears were “at the heart of everything”: an old clown whose age couldn’t be hidden by paint any more, a washed-up prostitute who still had to pretend she was a joy-girl, judges in tight collars too stupid to hand down just decisions. The face of Christ was everywhere, immeasurably sad, with eyes almost always closed, like the image pressed into Veronica’s handkerchief.

Then Steve took us into the next room and showed us that in 1930 a new element started showing up in Rouault’s pictures. It was a horizontal red line, like the balance-bar in a ballet school. Rouault put it behind clowns, acrobats, dancers—people who were liable to lose their balance and fall.

It was Rouault’s way of saying that even in a world racked by instability—and Steve showed us that Rouault’s was: born in 1871 in the cellar of a house that was being shot up by artillery, lived in France during World War I, fled south during World War II when the Nazis occupied Paris, knew all about the extermination camps and the Bomb and the cold war (he died in 1958)—even in a world racked by instability and miseries and tears, there is a red line of redemption, and this, as much as the tears, is a part of the truth of our experience.

It is hard to tell the truth.

Artists in the twentieth century sought like anything to tell the truth. That is why so many of their images are distorted and ugly. It was a distorted and ugly century. Most artists didn’t see any redemption in it, which is okay, because it can be hard to see. But what isn’t okay is the reflexive rejection of someone else’s vision of redemption just because I can’t see it. Artists do this as much as anyone else. Maybe that is partly why—as Sandra Bowden pointed out to us—Rouault was dropped from the sixth edition of Janson. It is sometimes hard for even artists to tell the truth and get elected.

On the drive back from

Thank the dear Lord that Rouault got it right. The misery and instability and danger of falling. The red balance bar at our hips.